Historical background

Cultural diversity is one of the most important historical and cultural attributes that makes Wrocław so distinctive. Though its rulers and borders have changed over the centuries, it was home for many nations and denominations owing to its location along various trade and migration routes. From the beginning, its Jewish settlers have shaped the landscape and spirit of the city. The documented history of their presence in Wrocław dates back 800 years but is undoubtedly older. Though periodically disrupted by persecution and expulsion, the Jewish presence was most beneficial for the city and primarily its economic development. Discrimination and isolation, however, did prevent the Jews from integrating fully into the cultural and political life of the city. The situation changed when Wrocław was incorporated into dynamic and modern Prussia and the golden age of German Jewry began.

Early Plans for the Synagogue

The Enlightenment came to Prussia at end of the 18th century – a period associated by Poles with the tragic partition of Poland. It was during this period that the Jewish population was gradually granted civic rights that allowed it to flourish. In 1790, for example, the Minister of Silesia, Count Karl Heinrich von Hoym, proposed the building of a public synagogue that was to serve the entire Jewish community and at the same time allow the authorities to have full control over the community.

This single synagogue was supposed to replace the houses of prayer scattered all over the city. However, the plan was blocked by orthodox Jews who regarded emancipation as a threat to their religious identity. In 1820, the Prussian government finally succeeded in forcing through its decision for the construction of the synagogue.

Sufficient funds were collected and a construction site was secured at 35 St Anthony Street, where the White Stork Inn had previously been located – hence the name of the synagogue. Some sources, however, claim it was named after a tannery belonging to the Stork family. The architectural blueprints were ready soon after but construction was once again postponed because of religious disputes in the divided Jewish community.

Completion

Plans for building the synagogue re-emerged in 1826 at the initiative of liberal Jews belonging to the First Society of Brothers. Construction finally began a year later and the most prominent individuals associated with it were the investor, Jakob hilip Silberstein, the master masons Schindler and Tschoke and the construction supervisor Thiele. The prominent German architect Carl Ferdinand Langhans designed the neo-classical building and the Jewish painter Raphael Biow decorated the interior. The first service took place on April 10, 1829, thirteen days before the official ceremonial inauguration.

For the next 18 years the temple was the Society’s private synagogue. Then in 1847 it became the main public synagogue for the growing, both in size and influence, liberal branch of the local Jewish community.

From Liberal to Orthodox

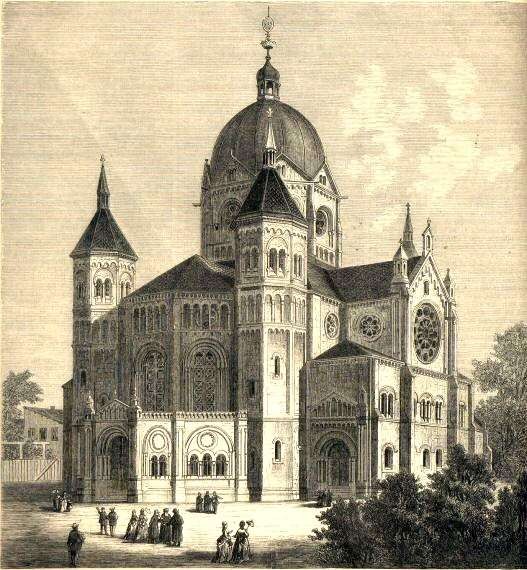

The majestic New Synagogue (Die Neue Synagoge) was erected in 1872 and shortly thereafter, the liberal Jews moved to this new house of prayer, leaving the White Stork synagogue to the Orthodox. Religious requirements forced the construction of three external staircases leading to galleries for women, disturbing somewhat the building’s composition. Reconstruction in 1905 by Paul and Richard Ehrlich resulted in the construction of neo-romanesque galleries for women made from reinforced concrete. The biggest and most radical improvement in the synagogue took place in 1929, the centenary of its existence. The exterior and interior were refurbished, central heating and electric lighting were installed, and a bimah (a pulpit for Torah reading) was erected in the center.

The Nazi Years

During the Crystal Night nazi pogrom on November 9, 1938, its close proximity to other buildings spared the White Stork Synagogue from the fate of the New Synagogue, which was burned to the ground. The White Stork synagogue continued to serve as a place of worship for both orthodox and liberal Jews until they were deported. The nazis later converted the site into an auto repair garage and warehouse for stolen Jewish property.

During the war, the courtyard was used as a gathering point, Umschlagsplatz, for the Jews before their deportation to the death camps. About half of them had managed by various means to escape from Germany before the arrests. The rest were murdered in concentration camps.

The Jewish population of Wrocław (Breslau until 1945) in 1925 had been approximately 23,000, making it the third largest Jewish community in Germany. From 1854 it had been home to the renown Jewish Theological Seminary, where orthodox and reform rabbis met for study and discussion. By 1945, the German Jewish community of Wrocław had ceased to exist, obliterated by the Holocaust.

A Polish Synagogue

On August 13, 1945, the Jewish Committee in Wrocław, representing the surviving Polish Jews that settled there after the war, petitioned the city’s mayor, Aleksander Wachniewski, for the return of the synagogue which at that time was occupied by the militia. After regaining possession, the Committee renovated the building and adapted it as a place of worship once again.

Subsequent waves of Jewish emigration leaving Poland, discrimination by the communist authorities and vandalism committed by “unidentified individuals” contributed to the gradual degradation of the building. During the sixties, the synagogue served as a prayer house and meeting place for the few thousand Jews still in Wrocław. The communist authorities closed the synagogue in 1966, claiming that it was a public hazard.

The Israelite Congregation in Wrocław intervened a year later and received permission to use the lower part of the synagogue for specific holidays.

Anti-Semitic Campaign of 1968

The year 1968 marked yet another dramatic moment in the history of the Wrocław Jewish community and its synagogue. The last wave of emigration provoked by the communist authorities’ antisemitic campaign put an end to services in the synagogue.

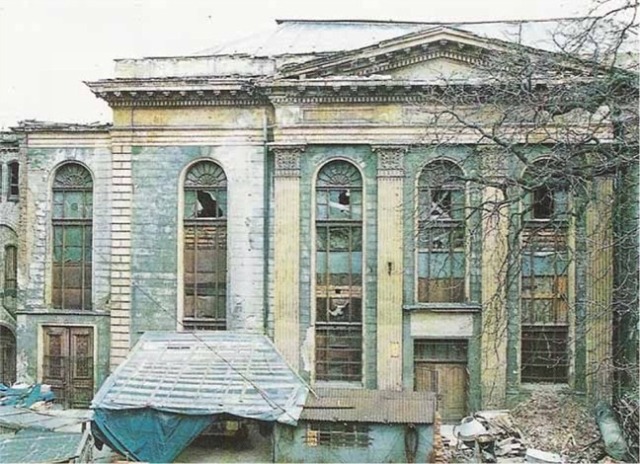

In 1974 the synagogue was confiscated by the government and given to Wrocław University to be converted into a library and lecture halls. The conversion began in 1976 but was soon abandoned and the building was left to deteriorate. After 1984, it was handed over to the city’s Center for Culture and Arts with plans for use as a venue for artistic performances. Ongoing devastation – mainly due to two fires – lead to yet another change of owner. In 1989, Wrocław Music Academy planned to convert the building into a concert hall. Reconstruction stopped shortly after the roof was removed and the abandoned building fell into a state of complete ruin. It was taken over by a private owner in 1992.

Democracy

Despite the political changes in 1989 and the positive attitude of the new, democratic local and national authorities, a few years still had to pass before the White Stork Synagogue was returned to its rightful owner, the Jewish community of Wrocław. Credit must be given to cardinal Henryk Gulbinowicz, the former metropolitan of Wrocław, who convinced the Ministry of Culture and Heritage to purchase the building from the private owner and return it to the reborn Jewish Religious Community in Wrocław on April 10, 1996.

One of the first to recognize the historic value of preserving the White Stork Synagogue was Eric F. Bowes, a Jew from Breslau who unfortunately passed away before the reconstruction was completed. The first Rosh Hashanah service took place in the ruined synagogue on September 1995.

Restoration by the Jewish Community of Wrocław

May 1996 marked the beginning of the restoration process supervised by Anna Kościuk, the head architect throughout the entire period. Work focused on replacing the roof, financed by the Foundation for Polish-German Cooperation. Plans for further renovation were based on existing arch ival pictures. In 1998, the third stage of the renovation was completed thanks to a donation from KGHM Polska Miedź S .A., the Lauder Foundation and the city of Wrocław.

In November 1998, 60 years after Crystal Night, a special commemorative service was held in the synagogue. The White Stork Synagogue Choir, conducted by Stanisław Rybarczyk, sang on that occasion for the first time. Among those present were Jerzy Buzek, the former Prime Minister of Poland, and Bogdan Zdrojewski, the former mayor of Wrocław, presently Minister of Culture and Heritage. It was the culmination of the struggle for reclaiming and saving the synagogue, lead by Michael Schudrich, chief rabbi of Poland, and Jerzy Kichler, the former chairman of the Jewish community in Wrocław and also of the Union of Jewish Religious Communities in Poland. Jerzy Kichler’s contribution and dedication to the basic restoration of the building was crucial. His work, together with David Ringel and Anatol Kaszen, was continued by the successive leaders of the Jewish commnity, Ignacy Einhorn and his deputy Klara Kołodziejska, as well as Karol Lewkowicz and Józef Kożuch.

The Bente Kahan Foundation

On May 7, 2005, the Wrocław Center for Jewish Culture and Education was established in the synagogue by its director Bente Kahan, the Norwegian Jewish performing artist. The following year, she founded the Bente Kahan Foundation together with Maciej Sygit, a socially engaged local entrepreneur. The Foundation joined forces with the Wrocław branch of the Association of the Jewish Religious Communities in Poland to restore the White Stork Synagogue, and further reconstruction was carried out with financial support from the city of Wrocław.

In 2008, the Bente Kahan Foundation received a European Economic Area grant (Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway) to complete the restoration of the historic building and its surrounding courtyard. The total cost of the project was about 2,5 million euro. Part of this was providedby the city of Wrocław, with the enthusiastic engagement of mayor Rafał Dutkiewicz and the city council, and the Union of Jewish Religious Communities in Poland, represented by president Piotr Kadlčik and vice president Andrzej Zozula. The project was lead by the Bente Kahan Foundation and supervised by Marek Mielczarek, its volunteer representative. The inauguration of the White Stork Synagogue took place on May 6, 2010 together with the opening of a permanent exhibit entitled History Reclaimed: Jewish Life in Wrocław and Lower Silesia.

Wrocław Center for Jewish Culture and Education

The Center in the White Stork Synagogue is run by the Bente Kahan Foundation in close cooperation with the Wrocław Jewish community and is supported by the city of Wrocław. It is a hub for exhibitions, film screenings, workshops, lectures, competitions and concerts, including educational theatre performances written and directed by Bente Kahan, that have been seen by more than twentyfive thousand youngsters from Wrocław and Lower Silesia. Many projects at the center are prepared together with the Jewish Studies Department of Wrocław University.

Havdalah concerts presenting a wide range of Jewish music have been held in the building since 1999. The Simcha Jewish Culture Festival takes place each spring and both events are organized by Stanisław Rybarczyk of the Pro Arte Foundation 2002. The synagogue, together with the Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches, is part of the Culture Path of the Four Denominations district, whose members organize cultural, educational and ecumenical events. This joint initiative is supported by the municipality of Wrocław.

The Wrocław Jewish Community Today

The community of Wrocław and Lower Silesia has over 300 members. It holds regular Shabbath prayer services, celebrates the Jewish holidays, and runs a kosher kitchen and dining hall. The community also offers social services for its elderly members, as well as a youth club and Sunday school for its youngest members. The head of the community since 2012 is Aleksander Gleichgewicht, and Tyson Herberger is its rabbi as of 2013.

Mikvah, Shtibl and Basement

Future plans for the synagogue include restoration of the historic mikvah (ritual bath), as well as a multimedia center in the basement.

Summer at The White Stork Synagogues – European Day of Jewish Culture – “Unfinished lives” concert